Breast cancer and HRT

To help with clarity, recent publications in this article are discussed in context with key clinical studies pre-dating them, which have influenced UK HRT prescribing. These were the 1997 CGHFBC re-analysis of 51 worldwide observational studies, previous publications from the randomised WHI study, the observational Million Women’s Study (MWS) and the 2015 UK National Institute for Health and Care and Excellence Menopause Guidance (NG23)

- The 1997 CGHFBC established a duration-dependent association of HRT with risk of diagnosis, emerging after 5 years’ exposure (an overall risk ratio of 1.35). This appeared greater with combined rather than unopposed HRT and fell following cessation (1)

- In 2002 and 2004, initial findings from the placebo-controlled, randomised WHI study confirmed an overall increased risk of borderline significance with continuous combined HRT (i.e. 0.625mg conjugated equine oestrogen [CEE] plus 2.5mg medroxyprogesterone acetate [MPA] (2) (3)

- In 2003, the observational MWS reported the risk of breast cancer to be increased with all HRT regimens, the greatest elevation in risk associated with combined preparations. In contrast with all other studies, the impact of HRT was observed with short-term use risk (i.e. 6 months to less than 2 years). This erroneous finding has now been attributed to ascertainment bias and underestimation of duration of HRT exposure but the adverse publicity the results generated caused a significant fall in HRT prescribing worldwide. (4)

In both the WHI study and the MWS, investigators placed emphasis on the use of risk ratios and percentage change in risk, which were misinterpreted. This could have been avoided by presenting findings using absolute numbers with framing. (5)

- The 2015 NG239 included an evaluation of the short-term outcomes of HRT, with use for up to 5 years on breast cancer outcomes. The clinical studies eligible for review were mostly observational and ranged from low to moderate quality at best and overall the findings did not differ significantly from those of previous evidence. (6)

As a consequence, clinical evidence predating more recent publications led to the following conclusions: (2,3,4)

- HRT with oestrogen alone (CEE, oestradiol, oestriol) was associated with no or little change in risk and may not be increased with low-dose vaginal oestrogen.

- Combined HRT, delivered by any route of administration, can be associated with an increased risk, which appears duration-dependent.

- Risk of diagnosis was not elevated in past users of HRT

- Risk was limited to lean women (i.e. not overweight or obese)

- There did not appear to be a dosage effect with oestrogen

- There may not have been an additive effect in women at elevated personal risk due to family history or high-risk benign breast condition.

In August 2019, a meta-analysis of over 100,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer in relation to the type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk was published by the Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (CGHFBC) (7). This also enabled the estimation of relative risks of breast cancer associated with different durations of exposure to, and formulations of, menopausal hormonal therapy (MHT) along with a breast cancer modelling algorithm based on degrees of family history.

In 2020, the long-term outcome report from the placebo-controlled, randomised Women’s Health Initiative study (WHI) was published. (8)

Based on this, the current evidence is now that (7,8):

1. In women with a low underlying risk of breast cancer (i.e. most of the population), the benefits of HRT for up to 5 years’ use for symptom relief will exceed potential harm:

- Unopposed oestrogen is associated with no, or little change, in risk but this may be influenced by age at initiation

- There is no evidence of a dosage effect with oestrogen

- Vaginal oestrogen is not associated with an increased risk

- Combined HRT can be associated with an increased risk, which appears duration dependent

- Whilst risk with continuous combined HRT may be greater than with sequential HRT, the difference in risk is small and may be offset by protection against endometrial cancer

- Avoidance of synthetic progestogens in combined preparations may minimise risk

- Risk is limited to lean women

- Risk associated with HRT (including past users) is less than other lifestyle risk factors for breast cancer

- In women with premature ovarian insufficiency, years of HRT exposure should be counted from the age of 50

- Communicating risk in terms of absolute excess risk with framing, minimizes misinterpretation.

2. In women at high risk or breast cancer survivors (7,8):

- There is no additive effect of HRT exposure in women at elevated personal risk due to family history or high-risk benign breast condition.

- If the use of HRT or vaginal oestrogen is considered, this should only be for the management of oestrogen deficiency symptoms after discussion with the woman’s breast specialist team

- Vaginal oestrogen can be used in women taking tamoxifen but not aromatase inhibitors.

The Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (CGHFBC) report also showed differences in data regarding estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative tumours and MHT stating (7):

- among current users, these breast cancer excess risks were definite even during years 1–4 (oestrogen-progestagen RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.52–1.69; oestrogen-only RR 1.17, 1.10–1.26), and were twice as great during years 5–14 (oestrogen-progestagen RR 2.08, 2.02–2.15; oestrogen-only RR 1.33, 1.28–1.37)

- oestrogen-progestagen risks during years 5–14 were greater with daily than with less frequent progestagen use (RR 2.30, 2.21–2.40 vs 1.93, 1.84–2.01; heterogeneity p<0.0001)

- for a given preparation, the RRs during years 5–14 of current use were much greater for oestrogen-receptor-positive tumours than for oestrogen-receptor-negative tumours, were similar for women starting MHT at ages 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, and 55–59 years, and were attenuated by starting after age 60 years or by adiposity (with little risk from oestrogen-only MHT in women who were obese)

- after ceasing MHT, some excess risk persisted for more than 10 years; its magnitude depended on the duration of previous use, with little excess following less than 1 year of MHT use

In 2019 the MHRA stated (9):

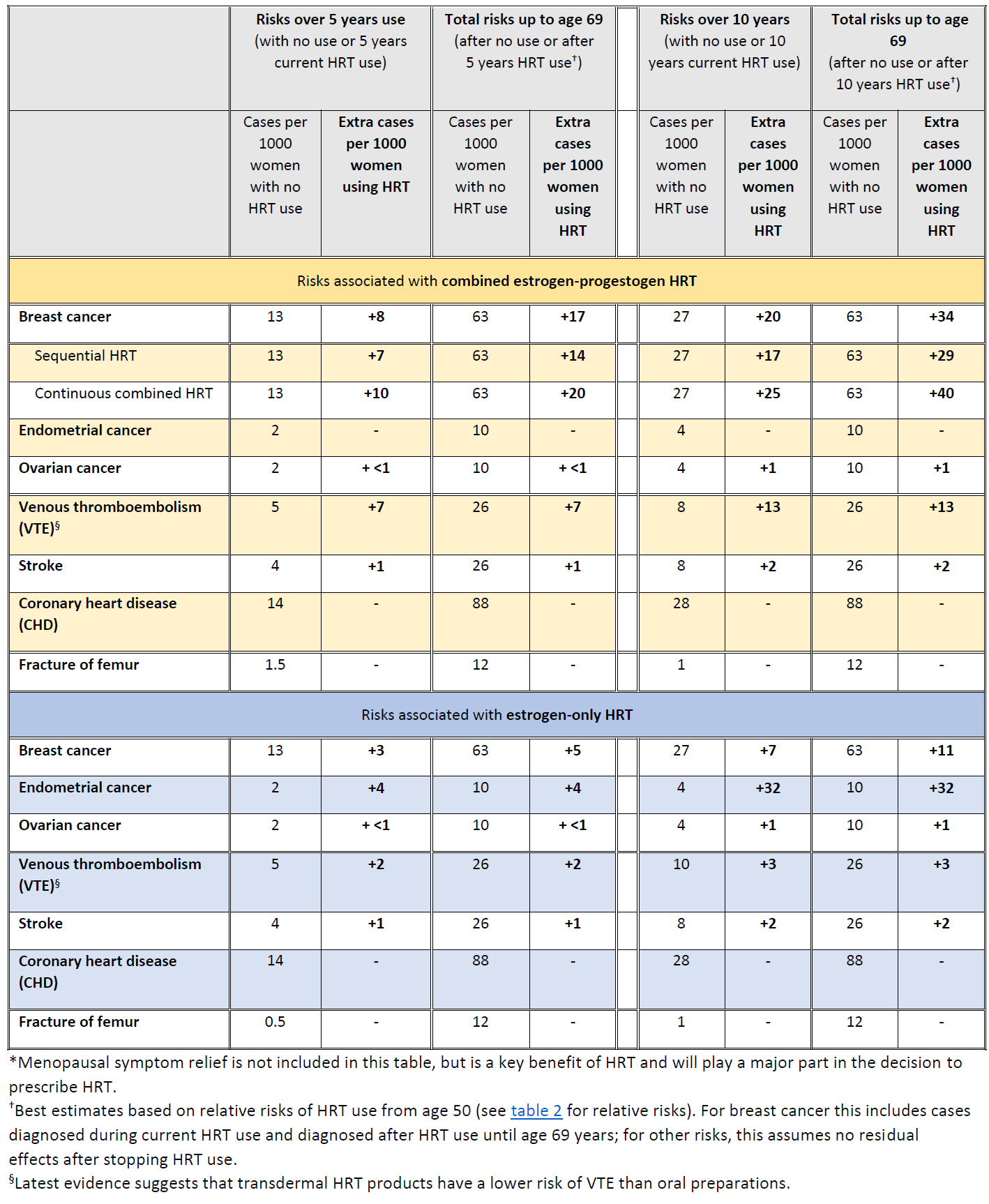

In the UK about 1 in 16 women who never use HRT are diagnosed with breast cancer between the ages of 50 and 69 years. This is equal to 63 cases of breast cancer per 1000 women. Over the same period (ages 50-69 years), with 5 years of HRT use, the study estimated:

- about 5 extra cases of breast cancer per 1000 women using estrogen-only HRT

- about 14 extra cases of breast cancer per 1000 women using estrogen combined with progestogen for part of each month (sequential HRT)

- about 20 extra cases of breast cancer per 1000 women using estrogen combined with daily progestogen HRT (continuous HRT)

These risks are for 5 years of HRT use. The number of extra cases of breast cancer above would approximately double if HRT was used for 10 years instead of 5.

The MHRA also stated (9):

- All forms of systemic HRT are associated with a significant excess incidence of breast cancer, irrespective of the type of estrogen or progestogen or route of delivery (oral or transdermal)

- There is little or no increase in risk with current or previous use of HRT for less than 1 year; however, there is an increased risk with HRT use for longer than 1 year

- Risk of breast cancer increases further with longer duration of HRT use

- Risk of breast cancer is lower after stopping HRT than it is during current use, but remains increased in ex-HRT users for more than 10 years compared with women who have never used HRT

- Risk of breast cancer is higher for combined estrogen-progestogen HRT than estrogen-only HRT

- For women who use HRT for similar durations, the total number of HRT-related breast cancers by age 69 years is similar whether HRT is started in her 40s or in her 50s

- The study found no evidence of an effect on breast cancer risk with use of low doses of estrogen applied directly via the vagina to treat local symptoms

The MHRA has summarised the risks of HRT with respect to breast, endometrial and ovarian cancer (9):

Summary of HRT risks and benefits* during current use and current use plus post-treatment from age of menopause up to age 69 years, per 1000 women with 5 years or 10 years use of HRT (9)

In 2020 a study of 98,611 women aged 50-79 with a primary diagnosis of breast cancer between 1998 and 2018 was done, matched by age, general practice, and index date to 457,498 female controls (10). It found that past long-term use of oestrogen-only therapy and past short-term (<5 years) use of oestrogen-progestogen were not associated with increased risk

A NIHR alert relating to this study states that (10):

- Most women took combined HRT, which was linked to a small increase in risk of breast cancer. The risk increased with:

- a woman’s age, with lower increases in risk for women in their 50s, compared to those in their 60s and 70s

- the duration of treatment, with lower increases in risk with HRT taken short-term (less than 5 years) than long-term (more than 5 years)

- current or more recent HRT treatment, which came with higher risks than past use (more than 5 years ago)

- the type of progestogen in combined HRT; with the highest risks with norethisterone and the lowest with dydrogesterone.

- The researchers stressed that some women who had never taken HRT would still get breast cancer. For example, if a group of 10,000 women in their 50s had never taken HRT, 26 women would still get breast cancer in a year. If all 10,000 women had recently taken combined HRT for less than 5 years, 35 would get breast cancer. So, in this large group of women, the HRT is linked to 9 extra cases of breast cancer in a year. That is less than one in a thousand women.

- The increased risk was mostly linked to combined HRT, and the type of progestogen made a difference. Risk increased similarly when preparations containing some types of progestogen (norethisterone, levonorgestrel, or medroxyprogesterone) were taken for more than a year. The lowest increase in risk was with dydrogesterone (another type of progestogen).

- Even if women took combined HRT long-term (more than 5 years), risks reduced after therapy was stopped. For women in their 50s, there was no extra risk of breast cancer with combined HRT that was stopped more than 5 years previously. There was little extra risk among women in their 60s and 70s.

- There was no increased risk of breast cancer:

- with any current HRT taken for one year or less

- with past use of oestrogen-only HRT, even if taken long-term

- with past use of combined HRT taken short-term

Breast cancer risk if there is a family history of breast cancer (11)

- A 2024 UK modelling study found that for a woman of 'average' family history taking no MHT, the cumulative breast cancer risk (age 50-80 years) is 9.8%, and the risk of dying from the breast cancer is 1.7%.

- in this model, 5 years' exposure to combined-cyclical MHT (age 50-55 years) was calculated to increase these risks to 11.0% and 1.8%, respectively.

- for a woman with a 'strong' family history taking no MHT, the cumulative breast cancer risk is 19.6% (age 50-80 years), and the risk of dying from the breast cancer is 3.2%. With 5 years' exposure to MHT (age 50-55 years), this model showed that these risks increase to 22.4% and 3.5%, respectively. (11)

- for example, for an ‘average’ 51 year old on combined HRT for 5 years, the likelihood of developing breast cancer attributable to HRT is 1 in 67

- for those with a strong family history, the respective likelihood is 1 in 30

- the authors conclude that although those with a significant (‘strong’) family history of breast cancer have a substantially increased baseline risk of developing breast cancer, most of the breast cancer incidence and mortality for this group will be attributable to their baseline risk rather than from the addition of HRT taken at age 50

- for example, for an ‘average’ 51 year old on combined HRT for 5 years, the likelihood of developing breast cancer attributable to HRT is 1 in 67

Note:

Any risk of breast cancer should be considered in the context of the overall benefits and risks associated with menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) intake including menopausal symptom control, improved quality of life and the long-term impact on bone and cardiovascular health. The decision whether to take MHT, the dose of MHT and the duration of its use should be made on an individualized basis after discussing the benefits and risks with women to help them make an informed choice about their health and care.

Reference:

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors for Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: Collaborative reanalysis from 51 individual epidemiological studies. Lancet 1997; 350: 1047–1060

- Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA 2002; 288: 321– 333

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR et al; Womens’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 2004; 291: 1701-12

- Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 2003; 362: 419–427

- Gigerenzer G. How innumeracy can be exploited, In Reckoning with Risk, publishers Penguin Group, 2003

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; Menopause; Clinical Guideline – methods, evidence and recommendations (NG23), 2015 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ ng23

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors for Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence, doi.org/10.1016/S0140- 6736(19)31709-X

- Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK et al. Association of menopausal hormone replacement therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised clinical trials. JAMA, 2020; 324: 369-380.

- MHRA (August 2019). Hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ 2020;371:m3873.

- Huntley C et al. Breast cancer risk assessment for prescription of Menopausal Hormone Therapy in women who have a family history of breast cancer. British Journal of General Practice 9 May 2024.

Related pages

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in patients with breast cancer

- Breast cancer

- Hormone replacement therapy

- Tibolone

- Heart disease and HRT

- Cancer risk if stopped HRT

- Clinical indications for HRT (hormone replacement therapy)

- NICE guidance - HRT and breast cancer risk

- Review of the evidence for breast cancer risk and HRT

Create an account to add page annotations

Annotations allow you to add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation. E.g. a website or number. This information will always show when you visit this page.