Investigations of a possible UTI in a child

In the neonate a full sepsis screen must be performed since the most likely source of the infection is from the blood. The older the child and the less severe the clinical picture, the less investigations are needed.

Urine must be viewed under a microscope and cultured.

UTI is a common bacterial infection that causes illness in children, in whom it may be difficult to diagnose as the presenting symptoms are often non-specific (1,2,3).

In children, the condition is often associated with renal tract abnormalities and is most common in males in the first three months of life as a result of congenital abnormalities. In older children, females are more commonly affected. Infection in pre-school boys is often associated with renal tract abnormality. Failure to diagnose and treat UTI quickly and effectively may result in renal scarring and ultimately loss of function. The phenomenon of vesicoureteric reflux, while predisposing children to UTI, may also be caused by UTI (1):

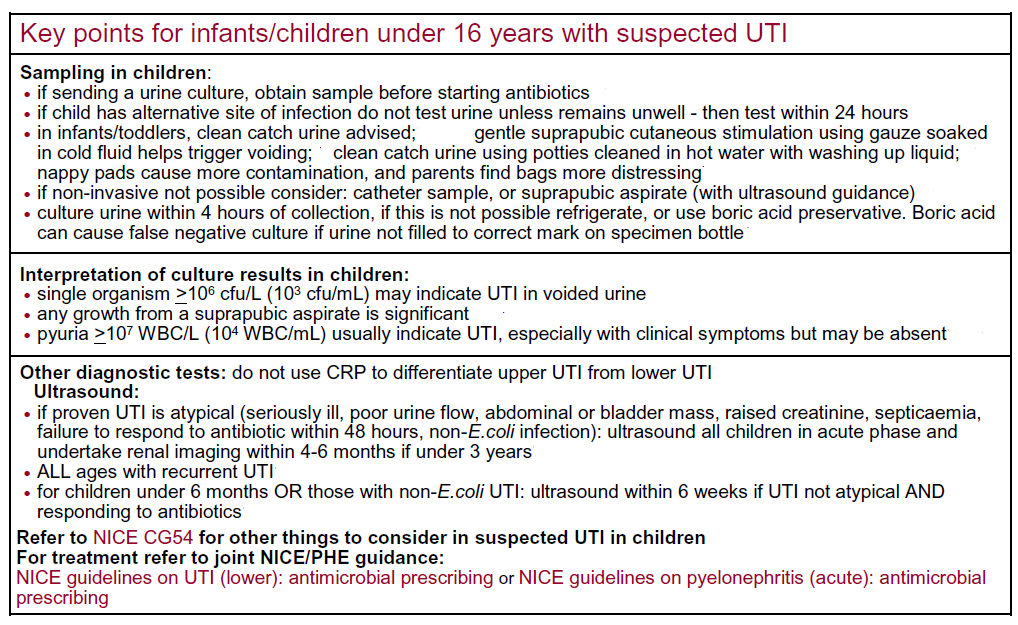

- Confirmation of UTI in children is dependent on the quality of the specimen, which is often difficult to obtain cleanly. The probability of UTI is increased by the isolation of the same organism from two specimens

. - Colony counts of more than 106 cfu/L (103 cfu/mL) of a single species may be diagnostic of UTI in voided urine

- Generally, a pure growth of between 107-108 cfu/L (104-105 cfu/mL) is indicative of UTI in a carefully taken specimen

- Negative cultures or growth of less than 107 cfu/L (less than 104 cfu/mL) from bag urine may be diagnostically useful. Counts of more than 108 cfu/L (105 cfu/mL) should be confirmed by culture of a more reliable specimen, either a single urethral catheter specimen or, preferably, an SPA

- Bacteriuria usually exceeds 108 cfu/L (greater than 105 cfu/mL) in SPAs from children with acute UTI, although any growth is potentially significant.

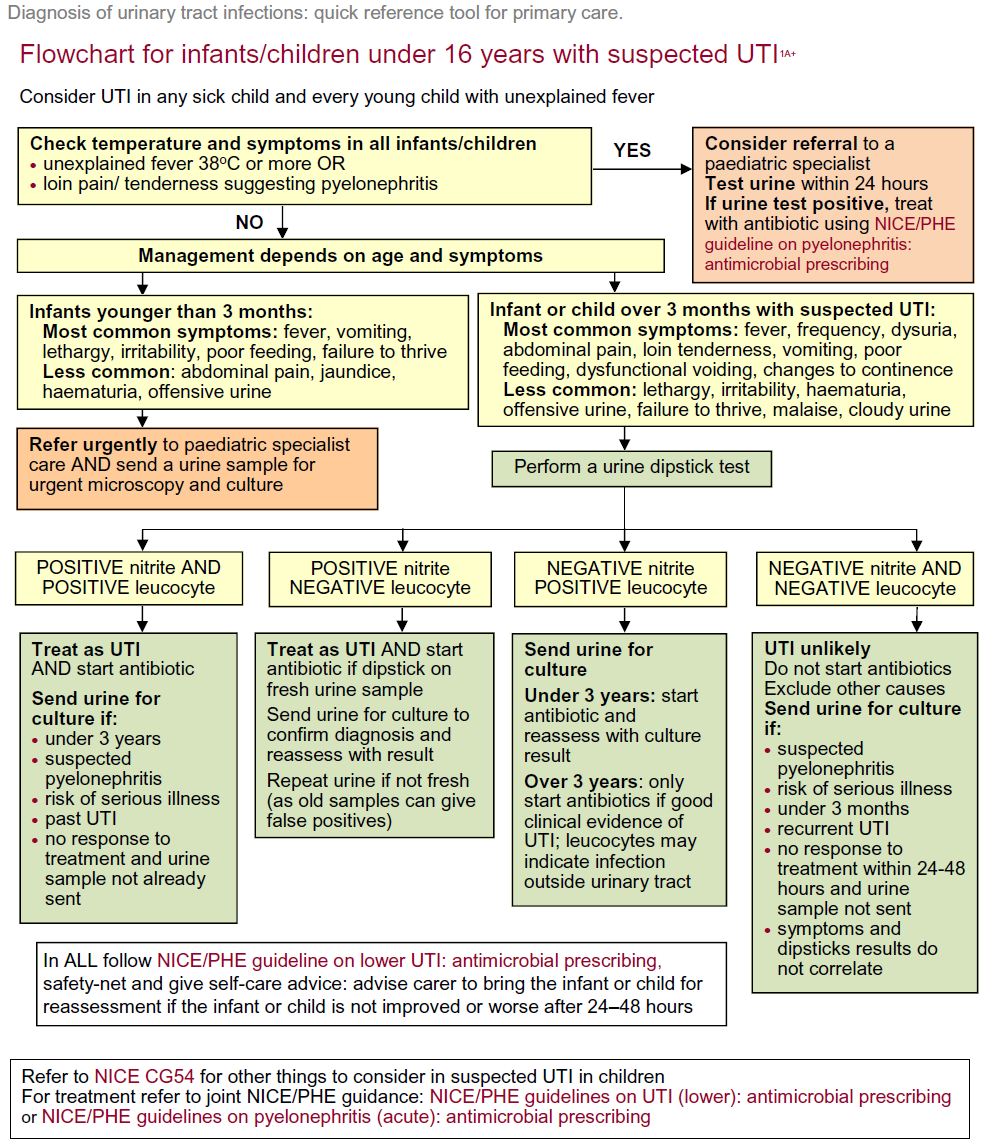

NICE however differentiate the need for further investigation based on the age of the patient and features of the UTI (2).

The guidance concerning urine testing also varies with respect to age of the patient (2).

Urine-testing strategy for infants younger than 3 months

- all infants younger than 3 months with suspected UTI should be referred to paediatric specialist care and a urine sample should be sent for urgent microscopy and culture

Use dipstick testing for infants and children 3 months or older but younger than 3 years with suspected UTI

If both leukocyte esterase and nitrite are negative:

- do not start antibiotic treatment; do not send a urine sample for microscopy and culture unless at least 1 of the criteria in recommendation apply

- Indication for culture

- urine samples should be sent for culture:

- in infants and children who are suspected to have acute pyelonephritis/upper urinary tract infection

- in infants and children with a high to intermediate risk of serious illness

- in infants under 3 months in infants and children with a positive result for leukocyte esterase or nitrite

- in infants and children with recurrent UTI

- in infants and children with an infection that does not respond to treatment within 24-48 hours, if no sample has already been sent

- when clinical symptoms and dipstick tests do not correlate

- urine samples should be sent for culture:

- Indication for culture

- If leukocyte esterase or nitrite, or both are positive: start antibiotic treatment; send a urine sample for culture

Urine-testing strategies for possible UTI in children 3 years or older (1)

- dipstick testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrite is diagnostically as useful as microscopy and culture, and can safely be used

- if both leukocyte esterase and nitrite are positive

- the child should be regarded as having UTI and antibiotic treatment should be started. If a child has a high or intermediate risk of serious illness and/or a past history of previous UTI, a urine sample should be sent for culture

- if leukocyte esterase is negative and nitrite is positive

- antibiotic treatment should be started if the urine test was carried out on a fresh sample of urine. A urine sample should be sent for culture. Subsequent management will depend upon the result of urine culture

- if leukocyte esterase is positive and nitrite is negative

- a urine sample should be sent for microscopy and culture. Antibiotic treatment for UTI should not be started unless there is good clinical evidence of UTI (for example, obvious urinary symptoms). Leukocyte esterase may be indicative of an infection outside the urinary tract which may need to be managed differently

- if both leukocyte esterase and nitrite are negative

- the child should not be regarded as having UTI. Antibiotic treatment for UTI should not be started, and a urine sample should not be sent for culture. Other causes of illness should be explored

- if both leukocyte esterase and nitrite are positive

PHE have suggested a flow chart for diagnosis of a UTI in a child (3):

Notes (2):

- evidence showed that a positive urine dipstick test for leukocyte esterase or nitrite in children 3 months or older but younger than 3 years greatly increases the likelihood of finding a positive urine culture. Sending only positive samples for culture offered a better balance of benefits and costs for these children than prescribing antibiotics and urine culture for all children

- the committee agreed that there are concerns about sepsis in infants under 3 months with suspected UTI, and usual practice is referral rather than the GP managing symptoms. So the committee recommended that all children under 3 months should be referred to specialist paediatric care and have a urine sample sent for urgent microscopy and culture

Reference:

- Public Health England. 2018. SMI B41: UK Standards for Microbiology 640 Investigations-Investigation of urine. United Kingdom

- NICE (September 2017).Urinary tract infection in children: diagnosis, treatment and long-term management

- Public Health England (August 2019). Diagnosis of urinary tract infections Quick reference tool for primary care.

Related pages

- Urine collection

- Urine testing

- Interpretation of urine microscopy in an infant or child

- Recommended imaging schedule for infants younger than 6 months

- Recommended imaging schedule for infants and children 6 months or older but younger than 3 years

- Recommended imaging schedule for children 3 years or older

Create an account to add page annotations

Annotations allow you to add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation. E.g. a website or number. This information will always show when you visit this page.