Chickenpox in pregnancy

- chickenpox occurs in pregnancy in about 3 per 1000 women in the UK

- about 90% of women have antibodies to varicella zoster virus - VZV - and therefore the fetus is not at risk of chickenpox even if the mother develops shingles during pregnancy (1)

- in the nonimmune pregnant woman, chickenpox is a potentially dangerous disease associated with fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality (1)

- chickenpox infection in pregnant women can lead to to varicella pneumonitis and severe maternal illness and it appears five times more likely to be fatal than in non-pregnant women (2,3)

- the risk is higher after 20 weeks of gestations in; those who smoke, have chronic lung disease, are immmunosupressed, or have more than 100 skin lesions (3)

- pneumonia is seen in up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox and appears to increase in severity with later gestation (4)

- although most women who have chickenpox in pregnancy give birth to healthy children, in other cases, the baby is harmed by in-utero infection or severe varicella of the newborn (2)

- fetal varicella syndrome syndrome is a known complication in the first half of the pregnancy (4)

- risk of the syndrome in children exposed to chickenpox in utero is around 0.5% if maternal chickenpox develops at 2-12 weeks of pregnancy

- 1.4% if it develops at 12-28 weeks

- 0% if it develops from 28 weeks onwards

- overall risk in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy is 0.91%

- fetal varicella syndrome syndrome is a known complication in the first half of the pregnancy (4)

- shingles in a pregnant woman does not pose a risk to the infant (3)

- chickenpox infection in pregnant women can lead to to varicella pneumonitis and severe maternal illness and it appears five times more likely to be fatal than in non-pregnant women (2,3)

Rationale for use of PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) for pregnant women at risk of chickenpox in pregnancy (7)

- chickenpox infection during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy can lead to fetal varicella syndrome, which includes microcephaly, cataracts, growth retardation limb hypoplasia, and skin scarring

- chickenpox can cause severe maternal disease and this risk is greatest in the second or early in the third trimester

- the rationale for PEP in pregnant women is two-fold:

- reduction in severity of maternal disease and

- theoretical reduction in the risk of fetal infection for women contracting varicella in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy

- in late pregnancy, PEP may also reduce the risk of neonatal infection

- however, given the risks of severe neonatal varicella in the first week of life, VZIG is also given to infants born within 7 days of onset of maternal varicella

- in the absence of PEP, the risk of developing varicella in susceptible contacts is high with 13 of 18 (72%) of seronegative pregnant women developing varicella following a significant exposure (7)

- further information about chickenpox in pregnancy is provided by the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Chickenpox in Pregnancy (Green-top Guideline No.13)

- antivirals are now recommended for post-exposure prophylaxis for all at risk groups apart from susceptible neonates exposed within one week of delivery (either in utero or post-delivery). Varicella zoster immunoglobulin (VZIG) is recommended for those for whom oral antivirals are contraindicated

Assessment of susceptibility (7)

- the administration of varicella zoster immunoglobulin (VZIG) is unlikely to confer any additional benefit for patients who already have varicella antibody (VZV IgG) and therefore VZIG is not recommended for individuals with adequate levels of VZV IgG. Assessment of susceptibility will depend on the history of previous infection or vaccination, and the underlying clinical condition

- for immunocompetent individuals including pregnant women, a history of previous chickenpox, shingles or 2 doses of varicella vaccine is sufficient evidence of immunity. In those without such a history, urgent antibody testing should be undertaken on a recent blood sample (booking blood samples are acceptable for pregnant women if available). PEP (post exposure prophylaxis) (antivirals or VZIG, if antivirals contraindicated) should be offered if VZV IgG is <100 mIU/ml

- for immunosuppressed patients, a history of previous infection or vaccination is not a reliable history of immunity and VZV antibody levels should be checked urgently. Individuals with VZV antibody levels of 150 mIU/ml or greater are unlikely to benefit from VZIG, and therefore individuals with VZV IgG <150 mIU/ml in a quantitative assay, or negative or equivocal in a qualitative assay should be offered PEP

- qualitative or quantitative antibody testing is required for all immunosuppressed patients where VZIG is being considered (such as individuals in whom antivirals are contraindicated)

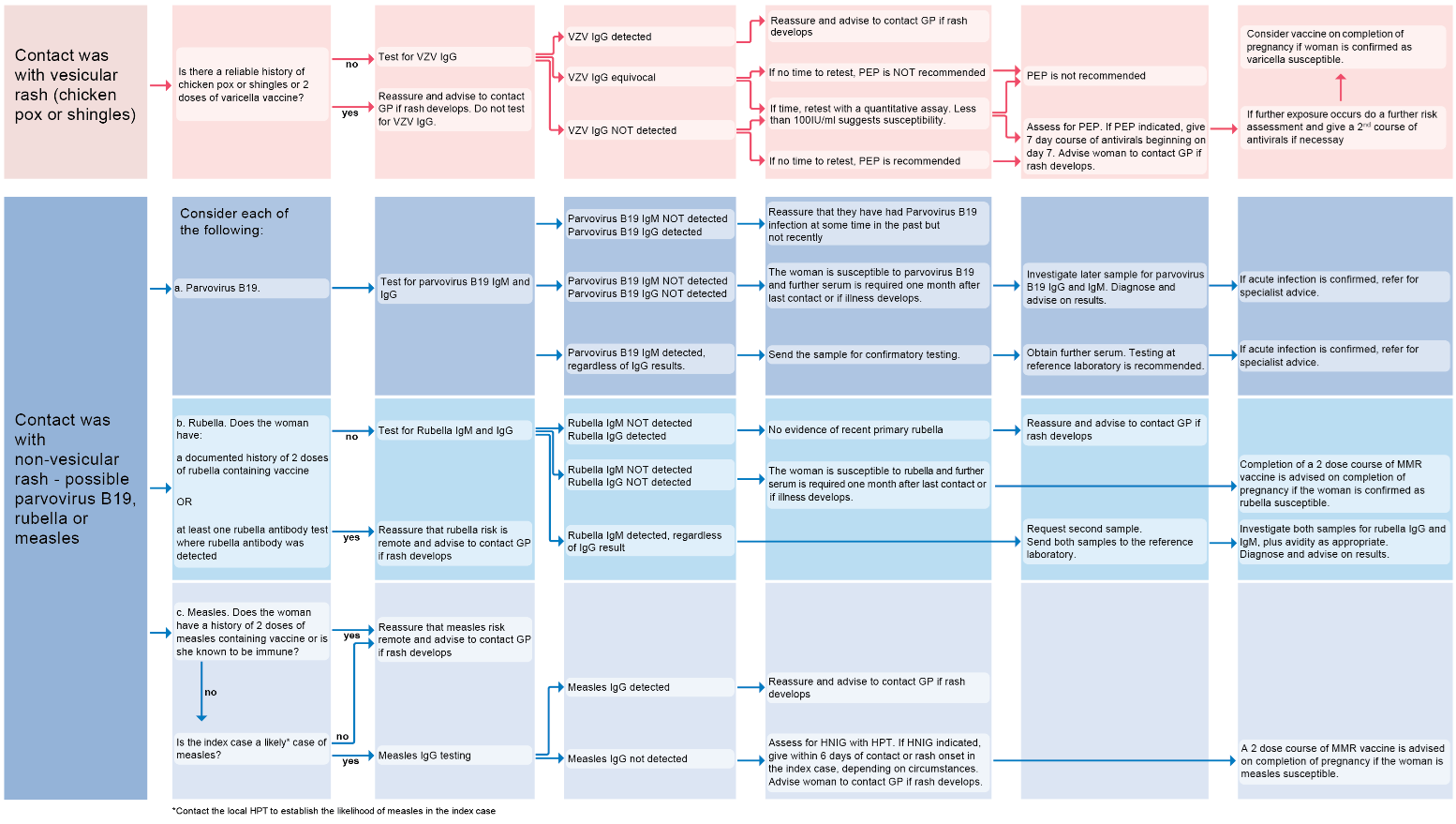

If considering an infectious cause for the development of the rash in pregnancy. A flowchart summarising contact with vesicular or non-vesicular rash (8):

Reference:

- (1) The Green Book. Immunisation against infectious disease. HMSO. London 1996.

- (2) Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2005;43(9):69-72.

- (3) Tunbridge AJ et al. Chickenpox in adults - Clinical management. Journal of Infection 2008;57:95e102

- (4) The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2007. Green-top Guideline No. 13 – Chickenpox in pregnancy

- (5) Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2005; 43(12):94-95.

- (6) BMJ 1993; 306: 1079

- (7) UK Health Security Agency. Guidelines on post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for varicella and shingles (January 2023)

- (8) UK Health Security Agency (July 2024). Guidance on the investigation, diagnosis and management of viral illness (plus syphilis), or exposure to viral rash illness, in pregnancy

Related pages

- Complications of chickenpox in pregnancy

- Management of chickenpox in pregnancy

- Breast feeding and isolation if maternal chickenpox

- Counselling of mother who has developed chickenpox in pregnancy

- Criteria for admission of a pregnant woman with chickenpox to a hospital

- Varicella vaccination of non-immune woman preconceptually

- Chickenpox

- Chickenpox (varicella) or shingles (zoster) post-exposure risk assessment: does the person need PEP (post exposure prophylaxis)?

Create an account to add page annotations

Annotations allow you to add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation. E.g. a website or number. This information will always show when you visit this page.