Management of acute cough in primary care

Last reviewed dd mmm yyyy. Last edited dd mmm yyyy

Managing acute cough

The important part in the management of an acute cough is to identify whether it is an indication of a

- life threatening illness such as foreign body aspiration, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism or

- non-life-threatening diagnosis such as respiratory tract infection, exposure to allergens or irritants (1).

Consider referring the following patients to a hospital (1):

- patients with lower respiratory tract infections with severe illness

- age over 80

- cormorbidity - upper respiratory tract infection together with asthma or COPD (1)

- suspected pulmonary embolism or malignancy (1)

Be aware that an acute cough (2):

- is usually self-limiting and gets better within 3 to 4 weeks without antibiotics

- is most commonly caused by a viral upper respiratory tract infection, such as a cold or flu

- can also be caused by acute bronchitis, a lower respiratory tract infection, which is usually a viral infection but can be bacterial

- can also have other infective or non-infective causes

For children under 5 with an acute cough and fever, follow the NICE guideline on fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management.

For adults with an acute cough and suspected pneumonia, follow the NICE guideline on pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management (3)

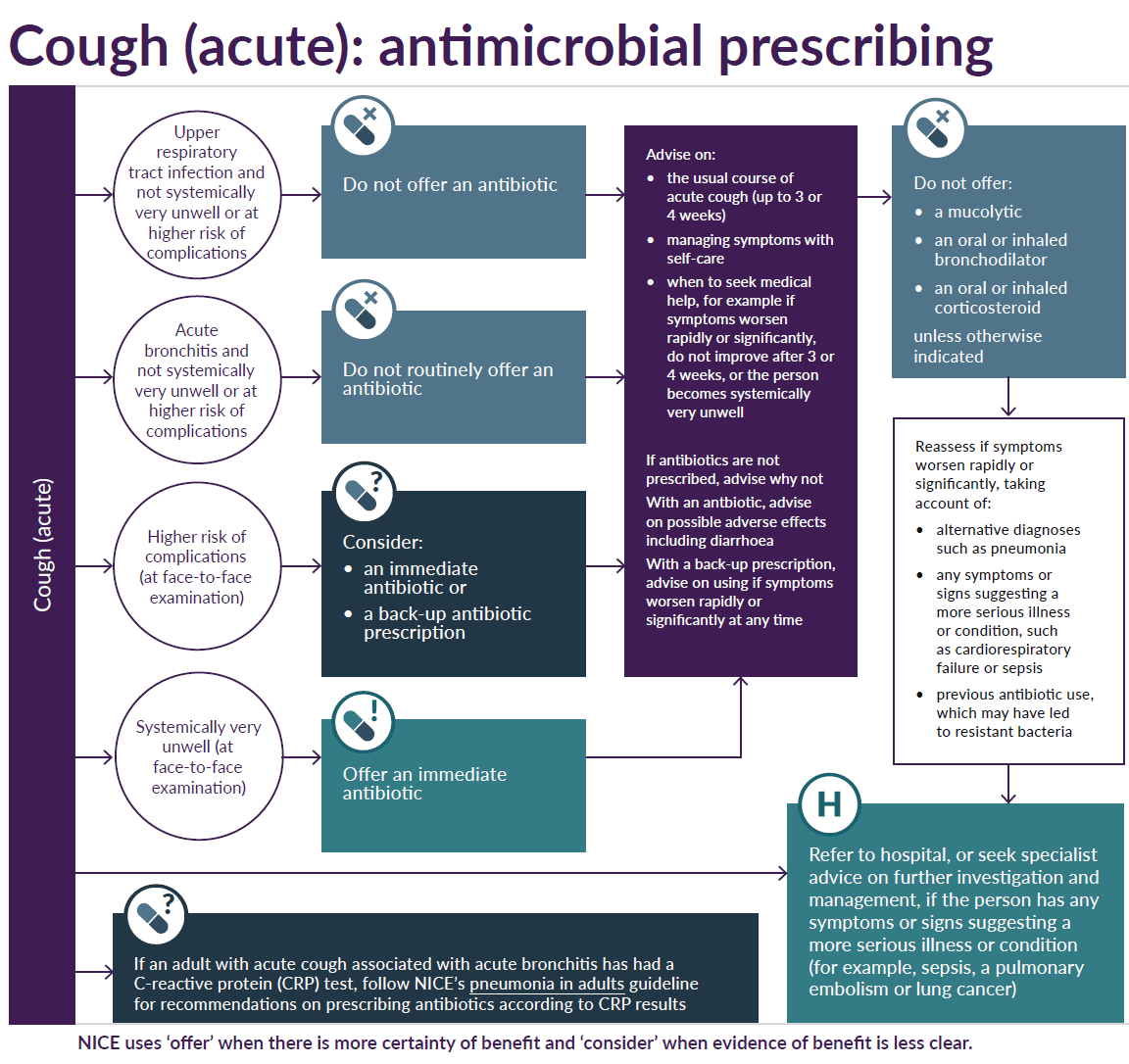

Acute cough - decision schemata (2,7):

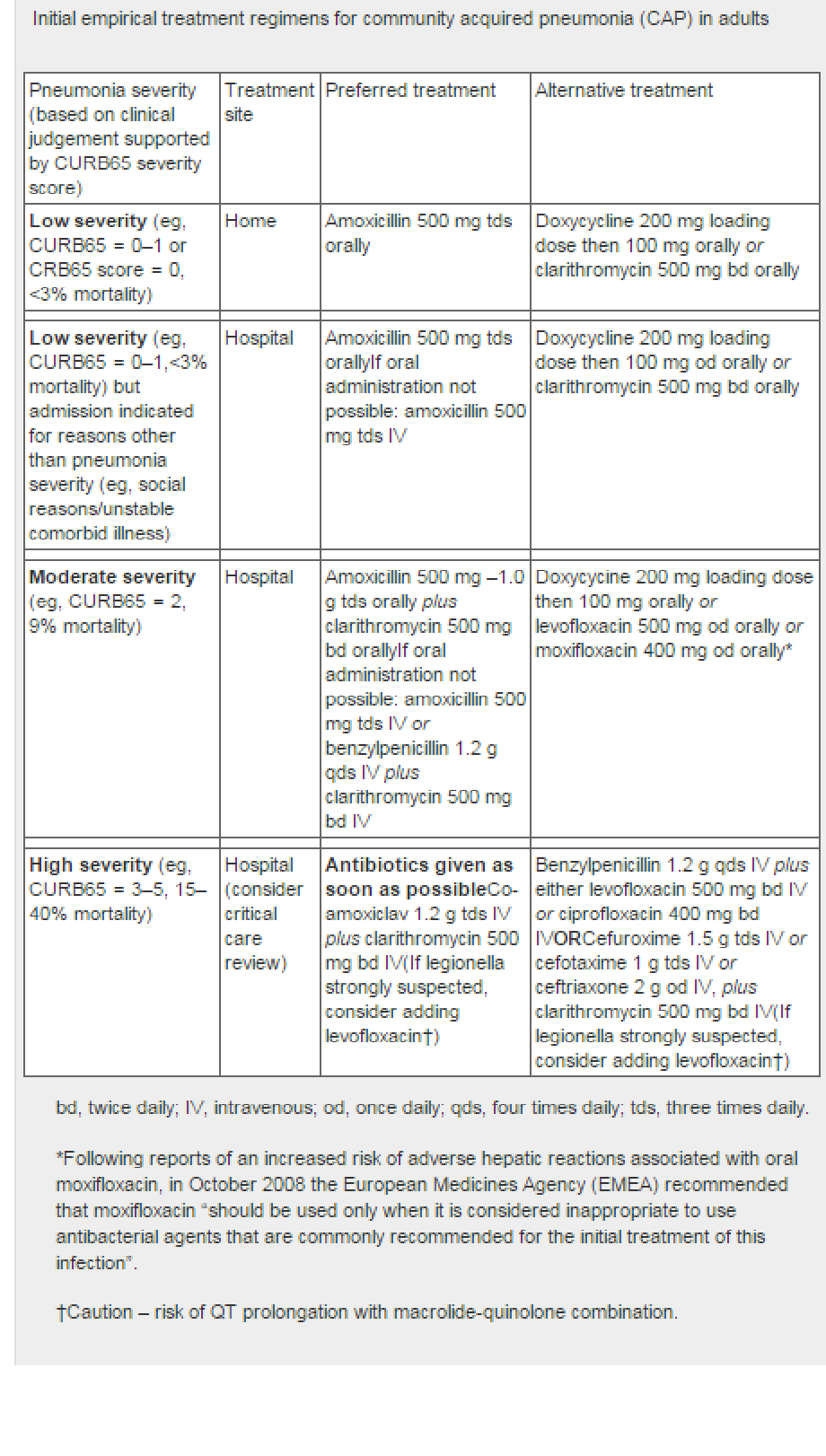

Pneumonia suspected:

- BTS guidance indicates where a patient should be treated, as well as suggested antibiotic regimen (4):

See linked item for choice of antibiotic in acute cough.

Notes:

- patients at higher risk of complications - these are defined as:

- if they:

- have a pre-existing comorbidity, such as significant heart, lung, renal, liver or neuromuscular disease, immunosuppression or cystic fibrosis

- are young children who were born prematurely

- are older than 65 years with 2 or more of the following criteria, or older than 80 years with 1 or more of the following criteria:

- hospitalisation in previous year

- type 1 or type 2 diabetes

- history of congestive heart failure

- current use of oral corticosteroids

- if they:

- the need of urgent medical admission (in an adult) can be based on the assessment of:

- respiratory rate - more than 30 breaths per minute

- blood pressure - systolic pressure <90 mmHg, or diastolic pressure <60 mmHg

- pulse - more than 130 beats per minute

- temperature

- altered level of consciousness (1,5)

- oxygen saturation level - < 92%, or central cyanosis

- peak expiratory flow rate - < 33% of predicted (6)

- reassess people with an acute cough

- if their symptoms worsen rapidly or significantly, taking account of:

- alternative diagnoses, such as pneumonia any symptoms or

- signs suggesting a more serious illness or condition, such as cardiorespiratory failure or sepsis

- previous antibiotic use, which may have led to resistant bacteria

- if their symptoms worsen rapidly or significantly, taking account of:

- referral and seeking specialist advice

- refer people with an acute cough to hospital, or seek specialist advice on further investigation and management, if they have any symptoms or signs suggesting a more serious illness or condition (for example, sepsis, a pulmonary embolism or lung cancer)

- refer people with an acute cough to hospital, or seek specialist advice on further investigation and management, if they have any symptoms or signs suggesting a more serious illness or condition (for example, sepsis, a pulmonary embolism or lung cancer)

- when an immediate antibiotic prescription is given, give advice about possible adverse effects of the antibiotic, particularly diarrhoea and nausea

- when a back-up antibiotic prescription is given, give advice about:

- an antibiotic not being needed immediately

- using the back-up prescription if symptoms worsen rapidly or significantly at any time

- Acute cough associated with an upper respiratory tract infection

- do not offer an antibiotic to treat an acute cough associated with an upper respiratory tract infection in people who are not systemically very unwell or at higher risk of complications

- do not offer an antibiotic to treat an acute cough associated with an upper respiratory tract infection in people who are not systemically very unwell or at higher risk of complications

- limited evidence suggests that antihistamines, decongestants and codeine-containing cough medicines do not help cough symptoms

Reference

- Dicpinigaitis PV et al. Acute cough: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cough. 2009;5:11

- NICE (February 2019). Cough (acute): antimicrobial prescribing

- NICE (December 2014).Pneumonia- Diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults

- 2015 - Annotated BTS Guideline for the management of CAP in adults (2009)

- Subbe CP. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001;94(10):521-6

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and British Thoracic Society 2009. British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline

- Public Health England (June 2021). Managing common infections: guidance for primary care

Related pages

- Choice of antibiotic in acute cough

- Lung cancer (NICE guidance for urgent referral for suspected cancer)

- Community acquired pneumonia (CAP)

- Cough for more than 2 weeks

- Cough associated with possible serious features e.g. wt loss

- Cough medicines

- Aromatic inhalations

- Nursing upright in respiratory congestion

Create an account to add page annotations

Annotations allow you to add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation. E.g. a website or number. This information will always show when you visit this page.