Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a serine protease which is usually specifically expressed by both normal and malignant prostate cells (1).

- PSA is a glycoprotein responsible for liquefying semen (dissolution of the seminal gel after ejaculation and hence found in ejaculate)

- expressed in both benign and malignant processes involving epithelial cells of the prostate

- PSA leaks out of the the prostate into the peripheral bloodstream due to an alteration in the architecture of the prostate in conditions such as prostatitis and BPE, as well as prostate cancer

- it is useful to detect cancer at an early stage or before symptoms develop resulting in early treatment of the cancer (2)

- PSA may help in diagnosis of prostate cancer

- however PSA values are likely to be increased with age and in conditions such as benign enlargement of the prostate, prostatitis and lower urinary tract infections (2)

Elevation of serum PSA is more a sensitive and specific indicator of prostatic carcinoma than prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP)

- PSA is raised in over 90% of cases when carcinoma is first detected by comparison to 50% for PAP.

- however, PSA lacks the required specificity to be a test for prostatic cancer as it is also increased in most patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy.

The most common PSA test measures the total amount of PSA (both free and protein bound) in the blood:

- an alternative test has been used which calculates the ratio of free: total PSA. Free PSA is associated with benign conditions while bound PSA is associated with malignancy. Hence a low ratio (<25%) may be indicative of cancer (2,6)

- evidence suggest that reflex testing with PSA isoforms, such as ratio of free to total PSA (f/tPSA) or complex PSA (cPSA), for men with PSA values <10 ng/mL (known as the diagnostic “grey zone”) could improve specificity and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies

- triage of men in the “grey zone” with tPSA 2 to 10 ng/ml using PSA isoforms could potentially reduce overdiagnosis and maintain a high cancer detection rate

PSA test is not diagnostic and require further investigations to confirm prostate cancer (2).

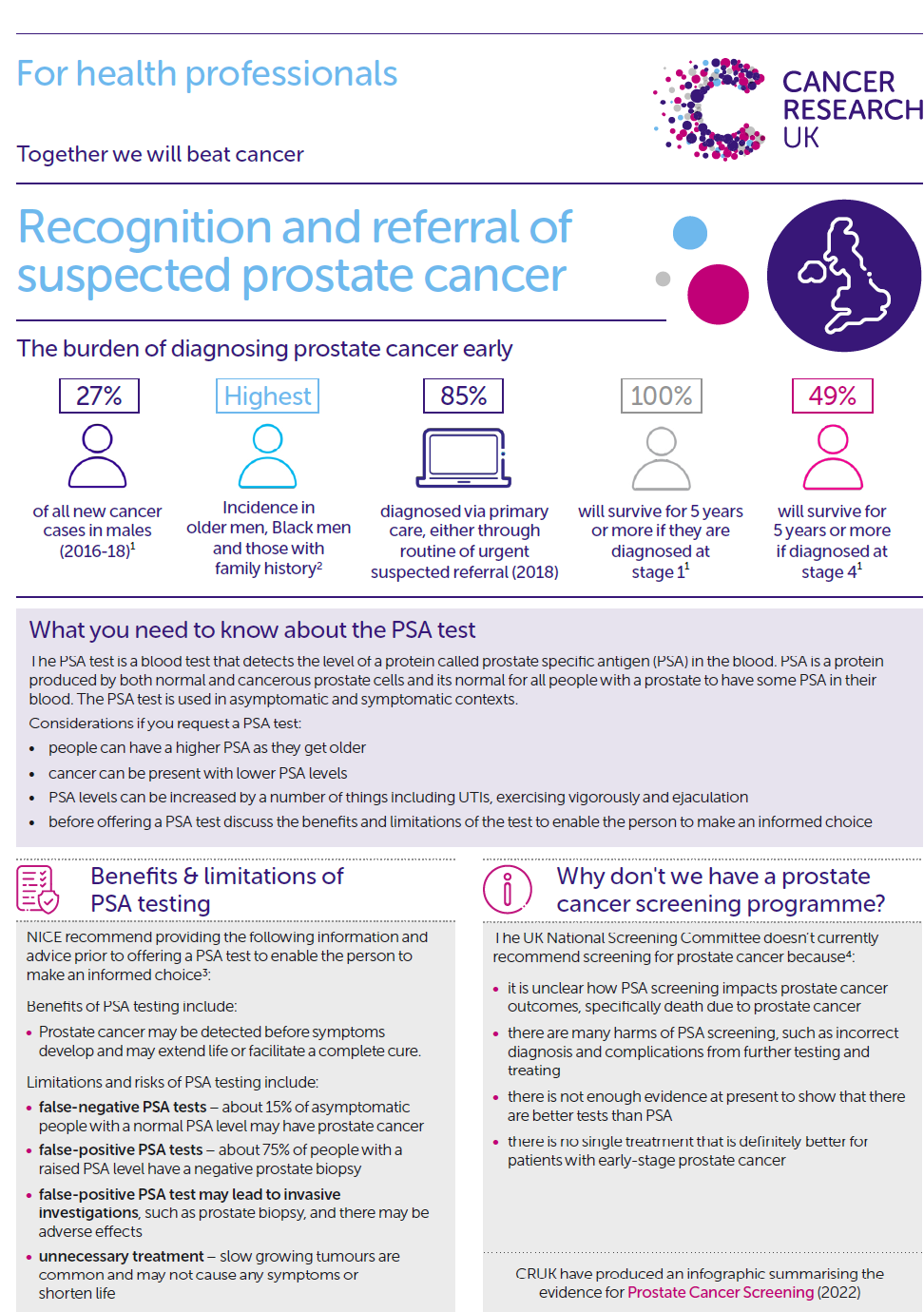

CRUK infographic summarising the evidence for Prostate Cancer Screening..Click here

Notes:

- before undertaking a PSA test, patients should be informed carefully as to why the test is done and its implications (2,3)

- a review states (3): (2,4) - however the PHE review states that "there are still significant gaps in our knowledge of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of clinically insignificant prostate cancers as well as identifying the optimum treatment" - also noted that the study did not use UK-comparable screening protocols, nor have the impacts on men’s symptoms and quality of life or costs been published (4)

- PSA aims to detect localised prostate cancer when treatment can be offered that may cure cancer or extend life. It is not usually recommended for asymptomatic men with less than 10 years life expectancy

- evidence suggests PSA screening could reduce prostate-cancer related mortality by 21%

- about 3 in 4 men with a raised PSA level (>=3ng/ml) will not have cancer. The PSA test can also miss about 15% of cancers - and 2% (1 in 50) will have high-grade cancer

- Before a PSA test men should not have:

- an active urinary infection

- ejaculated in previous 48 hours

- exercised vigorously in previous 48 hours

- had a prostate biopsy in previous 6 weeks

- not all men with increased PSA levels have cancer. Some will have low-risk disease (a relatively indolent tumour) that is unlikely to progress or require treatment. The low specificity of the PSA test has led to harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment in up to 50% of men (2,5)

- by the age of 80, about 80% of men will have evidence of cancer cells in their prostate. However, only 2 in 50 of all men will die from prostate cancer, which supports the evidence that men are more likely to die from other causes rather than from prostate cancer (2)

Reference:

- (1) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2008. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and treatment

- (2) Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme Information for primary care; PSA testing in asymptomatic men. Evidence document. NHS Cancer Screening Programmes, 2016

- (3) PHE (2016). Advising well men aged 50 and over about the PSA test for prostate cancer: information for GPs.

- (4) Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014;384(9959):2027-35

- (5) Ilic D, Neuberger MM, Djulbegovic M, et al. Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD004720

- (6) Catalona W et al. Use of the percentage of free prostate-specific antigen to enhance differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostatic disease: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. JAMA 1998; 279 (19): 1542–7

Related pages

- Practicalities of the PSA test

- Limitations of the PSA test

- Causes of a high PSA concentration

- Urological cancer (urgent referral guidance for suspected cancer)

- Reference range (PSA)

- PSA in health and disease

- Prostatic carcinoma

- Relationship between PSA and prostate cancer

- Prostate cancer screening

- Risk stratification for men with localised prostate cancer

- PSA kinetics

- PSA density

- PSA guidance for primary care relating to follow - up after diagnosis of prostate cancer

- BRCA2 and prostate cancer

- Finasteride in the prevention of prostate cancer

- Erectile dysfunction (ED) - NICE urgent cancer referral guidance

- PSA (free and protein bound)

Create an account to add page annotations

Add information to this page that would be handy to have on hand during a consultation, such as a web address or phone number. This information will always be displayed when you visit this page